Learning Spanish etiquette for dining, gyms, shopping, and socializing can be mystifying at first. Some things are self-explanatory, but others baffle me. Having a grasp of polite behavior will go a long way in avoiding a potential faux pas. Spanish social customs do differ at times, but learning by observing is my go-to strategy. What I’ve found below is by no means an exhaustive list and experiences do differ.

Dining etiquette

Common behaviors such as waiting for everyone to get their food before eating are observed here. It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, however. Once, I was with my cycling group at lunch when my tostada y tomate con atún y anchoa (essentially a bocadilla roll sliced in half, toasted, covered with a coating of pureed tomato then topped with tuna and anchovies) was brought out. Of course, I waited for the other orders to arrive. But seeing me waiting, my compañeros told me to start eating; it was OK.

Also remember, mealtimes are not rush hours. There’s the concept of sobremesa, around the table, with plenty of talk and no hurry. It is an extended social event. On one occasion, we were with a large group and stayed for over two hours at a restaurant. Meanwhile, the waitstaff brought in the tables and chairs in preparation for shutting down for the afternoon. But they said there wasn’t a problem with us continuing our conversation and staying at our table past closing.

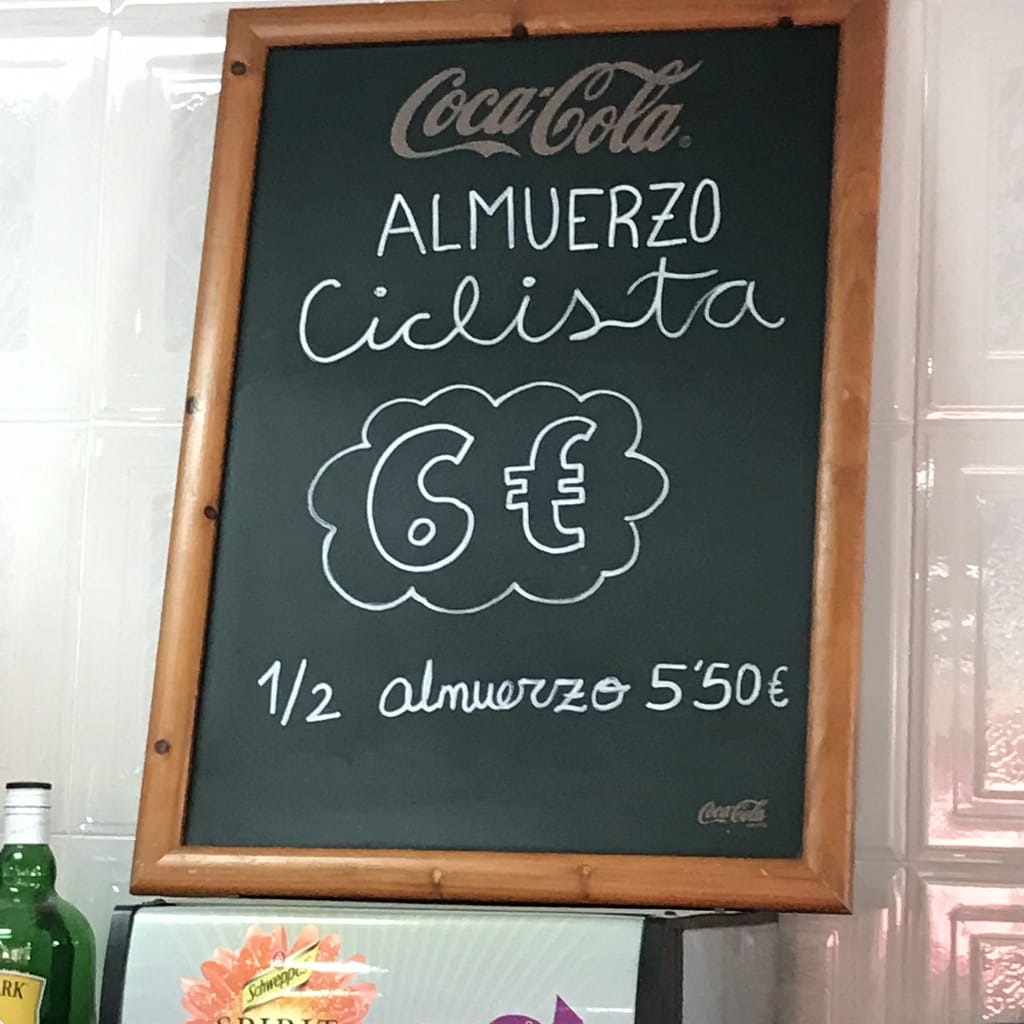

Desayuno is breakfast, which is a light affair usually consisting of a cup of coffee and a pastry (though I have seen beer and wine also consumed), then there’s the merienda (mid-morning snack) before the almuerzo (lunch), which usually occurs from 1-ish to 4-ish o’clock. By the way, almuerzo is the real meal of the day, with some restaurants offering primeros and segundos platos in addition to postre (dessert) and coffee. La cena, or dinner, is a series of small dishes (tapas) spread out over several hours in the late evening. In this manner, the patrons can navigate between bars and restaurants, dine and drink a bit at each, meet friends, and plan the rest of the night’s activities.

Ultimately, look out for “la de la vergüenza” (that of shame) or last morsel remaining on the plate. As in the U.S. it’s not considered good manners to take the last peice. In Spain, usually someone will finish it off, but not without some joshing and encouragement from the other diners.

Gym etiquette

I would not consider myself a gym rat by any means. Working out is my long-term plan to maintain my muscle mass and body health. In doing that, I’ve learned a thing or two about how to act in a gym. In Spain, it’s different in some key areas. Someone hovering nearby while you are doing your sets can be disconcerting. When you finish and clear the machine, they swoop in to claim it.

Then there’s marking the territory, usually a machine, with a towel or water bottle while going off to do another activity. I think the idea is to make sure they do their workouts in order, such as with opposing muscle groups (e.g. leg presses followed by hamstring extensions) and don’t want that flow interrupted.

Some simularities to the U.S. are the hoarding of a series of dumbbells like squirrels gathering nuts for the winter. I’ve seen the weight rack stripped clean, with its contents scattered around a patron at a bench. I thought the polite thing to do was to take the weights you needed for that set and after completion return them to the rack. Then get the next weights in the sequence.

Finally, the fashion.

Bare midriffs and shoulders aren’t forbidden. Really tight bike pants on both males and females leave very little to the imagination. When I first arrived here, I did a double-take. But now, I really don’t notice—too much. Sartorially, there doesn’t seem to be too much banned, but I have seen at least two rules enforced. First, no bare heads in the pool. I don’t know if they make bald-headed people wear a swim cap, but there weren’t any exceptions listed. Second, I saw someone chastised by the staff for wearing ropa de calle – street clothes – while working out. But that rule is inconsistently applied. Conversely, gym clothing is not (usually) a fashion choice for the street.

Grocery-shopping etiquette

Unlike in the U.S., grocery stores in Europe don’t try to carry everything. Looking for light bulbs? Head to the ferretería or hardware store. What’s available at the supermercado is limited. You won’t find an aisle just devoted to cereales. Many stores in Spain are in compact, urban spaces and just don’t have room to carry a vast assortment. Happily, it does make the decision-making simpler. Cereal really is an American thing, or, at least, not the go-to breakfast in Spain.

Here’s what you will find: gloves. Shoppers don’t touch the produce without guantes. You can put the used ones in a nearby receptacle to be recycled. If you want to irritate the other shoppers and merchants, paw over the vegetables and fruits by poking and prodding them with your bare hands. If you touch it, you buy it.

And this one surprised me during one of my initial grocery shopping trips. If you are going to be at a spot for a while, there’s a marked-off area in the middle of the produce department. That’s for your shopping cart so you don’t block access to the veggies as you leisurely peruse the various items while slowly pushing the cart along.

Want to know more? My wife wrote about her experiences while shopping in Italy, but many of her tips also are applicable to Spain.

Living in a close-knit community

Etiquette means behaving yourself a little better than is absolutely essential.

Will Cuppy

Etiquette is how interactions between people are smoothed. Usted and Ustedes, the formal sense of “you” in Spanish can be thing at times. But for the most part, among my peers, the more familar tú and vosotros (you and you all) suffices. But in a new social situation, I listen to how I and others are addressed to get a sense of the pronoun to be used.

Living in Rome years ago, we’d hear the cry “Attenti alla cacca,” (watch out for poop!). Here in Spain, that’s my pet peeve (pun intended). It’s the problem of people not picking up after their dogs. This might apply to cats too, but I don’t see those out on leashes using the sidewalks to relieve themselves.

Speaking of sidewalks: chewing gum. It gets stuck to shoes, wrapped around my bike tires, spun into the gearing mechanism. It’s just irresponsible and should be banned. OK, that’s a little draconian but observe any well-trafficked public space and look at all the gobs of gum covering the surface. Bleeh!

And, if you’re lucky enough to be invited by a Spaniard to any personal event, be aware of a few things. It won’t be at home. Most apartments are small, and socializing is done in the cafes. Don’t ask what they do for a living. They usually won’t ask what you do either, so leave your work title at home. Work doesn’t define Spaniards – it’s a means to an end.

It’s not what you know; it’s whom you know

Spain really is a country of relationships. These are centered around the family. Pick any Sunday afternoon and pass by the outside seating of a restaurant. You’ll see and hear an extended family – grandparents, children, grandchildren – gathered around a large table. This is the prime unit of Spanish society.

And they have known many of their friends all their life. Going to school with them and maybe working with them. It’s a bond that’s difficult to forge but easy to break. My wife’s hairstylist, who grew up in Valencia, moved away for a time. Upon her return, she found she was now outside her previous social group and had a difficult time making new friends.

Surprisingly, I couldn’t find a cycling group in Rome years ago. Being in school full-time didn’t leave a lot of opportunity to meet up for organized rides. It was a similar situation here in Valencia. I asked at the bike shops, but this was near the end of the Covid pandemic and there wasn’t anything really scheduled. So, a lot of my initial riding consisted of short- and long-training sessions by myself.

I would spot other cyclists, but they were heading in the opposite direction. A wave of the hand, a nod of the head, that was it for a connection. During one of my longer rides, I passed a cyclist, who then dropped in behind me and we started trading pulls. That’s when riders take turns at the front, allowing the others to rest in the slipstream. Soon we got to talking in mixture of Spanish and English and he told me about a group that rode on Saturdays from a nearby university.

Working up my courage, remembered my experience in Italy, and made sure I knew the name of the person inviting me to ride with the group. That was the magic word. I was asked several times who I knew in the group. Replying with the name was all it took. That and being well versed in the universal rules of cycling etiquette. But that’s a story for another day.

Every day is another opportunity to learn something new. Since I’m still struggling with my Spanish, I’ve found that the old adage of “You learn more with your mouth closed and ears open” is good advice.

Leave a Reply